Tek line of succession

Tektronix owned the company for almost 26 years and in that time it saw 10 different "heads of state." Some held the title of General Manager, a couple ran it as Vice Presidents, and twice it was run remotely by someone with Tektronix up in Oregon. From the beginning of the Tektronix era there were at least two layers between the top person at the Group and Tektronix's office of the President.

Jim Ward

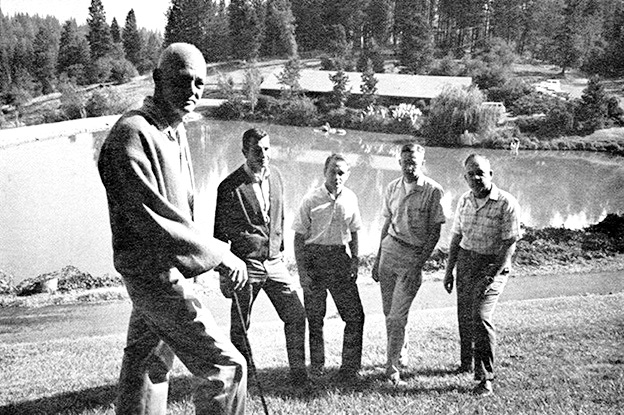

Left to right: Doc Hare, son Steve Hare, center Jim Ward, Bill Rorden, and Bob Cobler

Jim Ward was an accountant who worked for an San Francisco based firm that Dr. Hare employed to keep the company's books. Hare eventually hired Jim to serve as the company's CFO. When Hare left the company, he promoted Jim to the role of head of the company, with the title of Executive Vice President. But the President title was held by another, one who had been instrumental in buying the Group.

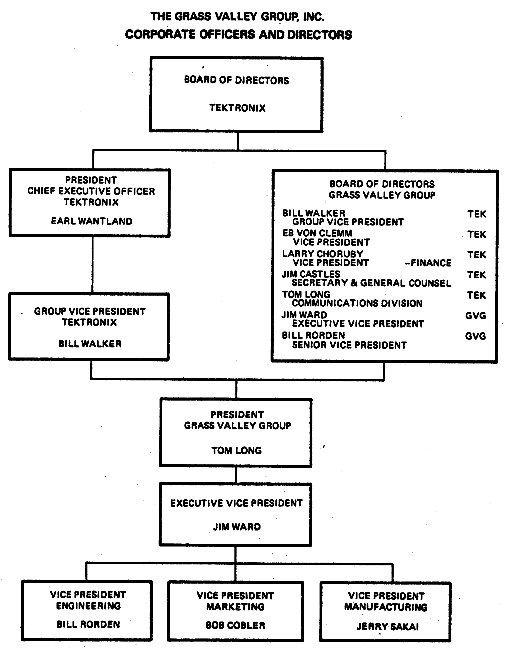

Tom Long

Tom Long, was the head of the Communications Division of Tektronix, which had TV and video products. In that position he also held the rank of Vice President. He along with the Vice Presidents of the other three divisions reported to the Group Vice President, who in turn reported to Tektronix's Office of the President, which included the CEO and COO. Long oversaw Grass Valley. Tom Long was generally protective of the group and tried to limit Tektronix meddling in the groups day-to-day operation, and as a level above he never ran GVG directly.

GVG Org chart November 77

Long started with Tektronix in 1960 as a Field engineer, in Chicago. The next year he transferred to Dayton, Ohio and went to college at the University of Dayton, and received a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering, in 1965. He continued on and got his Master of Business Administration from the same school in 1967. He then moved to Beaverton and became a marketing manager. In 1971 he became the engineering manager for the Instruments Division, and advanced to vice president, and general manager of the Communications Division in 1973. When the Group was bought he assumed the Grass Valley President's title also.

Ward and Long did not hit it off. Ward refused to provide Long with detailed operational information he wanted regarding the Group.

(Was any of this in deference to Dr. Hare?)

![]() The problem was that Ward used what is known as cash accounting, where payment receipts were recorded during the period in which they are received, and expenses are recorded in the period in which they are actually paid. In other words, revenues and expenses are recorded when cash is received and paid, respectively. Which was out of step with what Tektronix did. Also, instead of standardize Profit and Loss statements Ward would look at the end of the year at how much money was on hand, and if it was more than there was at the start of the year, the company must have made a profit. While Long was very set on allowing Grass Valley to run independent of Tektronix, he had to report financials to his superiors, and Ward's insistence on continuing under Hare's rules did not mesh with Tektronix's. Long made the change in 1978.

The problem was that Ward used what is known as cash accounting, where payment receipts were recorded during the period in which they are received, and expenses are recorded in the period in which they are actually paid. In other words, revenues and expenses are recorded when cash is received and paid, respectively. Which was out of step with what Tektronix did. Also, instead of standardize Profit and Loss statements Ward would look at the end of the year at how much money was on hand, and if it was more than there was at the start of the year, the company must have made a profit. While Long was very set on allowing Grass Valley to run independent of Tektronix, he had to report financials to his superiors, and Ward's insistence on continuing under Hare's rules did not mesh with Tektronix's. Long made the change in 1978.

In the fall of 1978, Jim Ward convened an impromptu "managers meeting" in which he introduced Dave Friedley as his replacement. The attendees of this meeting were stunned at the news, because no one had ever heard the name Dave Friedley before, let alone met the man, and there was no sense of change coming. It was reported that Ward was very gracious and professional. He indicated that Tektronix had offered him the opportunity to stay on as CFO, but he declined their offer. He said that he felt it would be better to move on. As we will see he eventually joined other ex-Group alumni Merv Graham and Mike Patten at Graham-Patten Systems.

In the fall of 1978, Jim Ward convened an impromptu "managers meeting" in which he introduced Dave Friedley as his replacement. The attendees of this meeting were stunned at the news, because no one had ever heard the name Dave Friedley before, let alone met the man, and there was no sense of change coming. It was reported that Ward was very gracious and professional. He indicated that Tektronix had offered him the opportunity to stay on as CFO, but he declined their offer. He said that he felt it would be better to move on. As we will see he eventually joined other ex-Group alumni Merv Graham and Mike Patten at Graham-Patten Systems.

Long left the company in April 83. Here Dave Friedley presents a volleyball autographed by many of the Group's employees. He was an avid player. He was not gone for long, no pun intended, as the east and his new company was not a good fit for him. As we will see in the next chapter he was back in the following year.

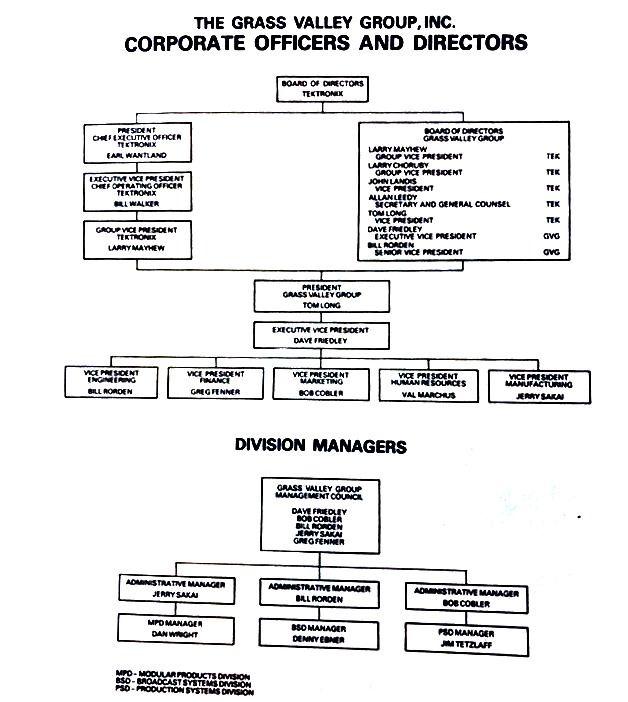

GVG Org chart a month before Tom Long leaves

Dave Friedley

During his tenure as the head of GVG, Dave Friedley sought to reshape the GVG culture to conform to Tektronix's idea of what it should be: more structured and less free-wheeling than it was before he arrived.

An electrical engineering graduate of Cornell University, Friedley worked in sales engineering, and marketing for Gen Rad (formerly General Radio Company) prior to joining Tektronix as marketing manager for spectrum analyzers in 1974. In the following four years he became the manager for frequency domain instruments before being tapped to be the Group's General Manager.

Friedley spent the first year kind of holed up in his office and then finally came out and got acquainted. Over time, he had a polarizing influence, he was either considered one of the best leaders the Group had, or one of the worst.

One of the first things Friedley did was bring down Greg Fenner as the Group's CFO. Fenner had played football for Purdue and those that did not like him claimed he suffered one too many head butts. It was claimed that he got the job because he was a member of Big Brothers-Big Sisters in Beaverton and helped Tom Long's son off of drugs.

Friedley was known to have a temper, and some claimed he liked pitting one group against another.

A Grass Valley engineer recalls having dinner with Friedley in New York City. Friedley ordered Lamb Chops. The waiter brought the dinners and his dinner companion said, "Hey, they didn't bring you any mint jelly." Friedley laid into the waiter and the chef for serving lamb without mint jelly.

Another story was that after building seven was finished, Friedley moved into the building and his area was nicely carpeted, while the engineering areas in the building were bare concrete. He was asked why this was the case at an all hands meeting. He responded because "Engineers are Dirty People." Kind of tone deaf many thought, which went over like a led balloon. One person acted on it. The next weekend someone brought in thousands of fleas and placed them in the carpet.

As mentioned earlier Friedley fired Mike Patton and Merv Graham, over the pair honestly reporting that they would not get the 300 to the 1979 NAB. As we covered in the chapter 10, it was a project that was breaking much new ground, and much of the engineering to meet the targeted external specs, had not been developed yet. In fact much of the basic strategy and approach was still unknown. The pair went off to start their own company, which we will see later. That company was soon joined by Jim Ward.

But as General Manager he did a lot of good. Friedley oversaw the introduction of EMEM, spearheaded by Bruce Rayner, and funded Birney Dayton's development of hybrids, both of which were covered earlier.

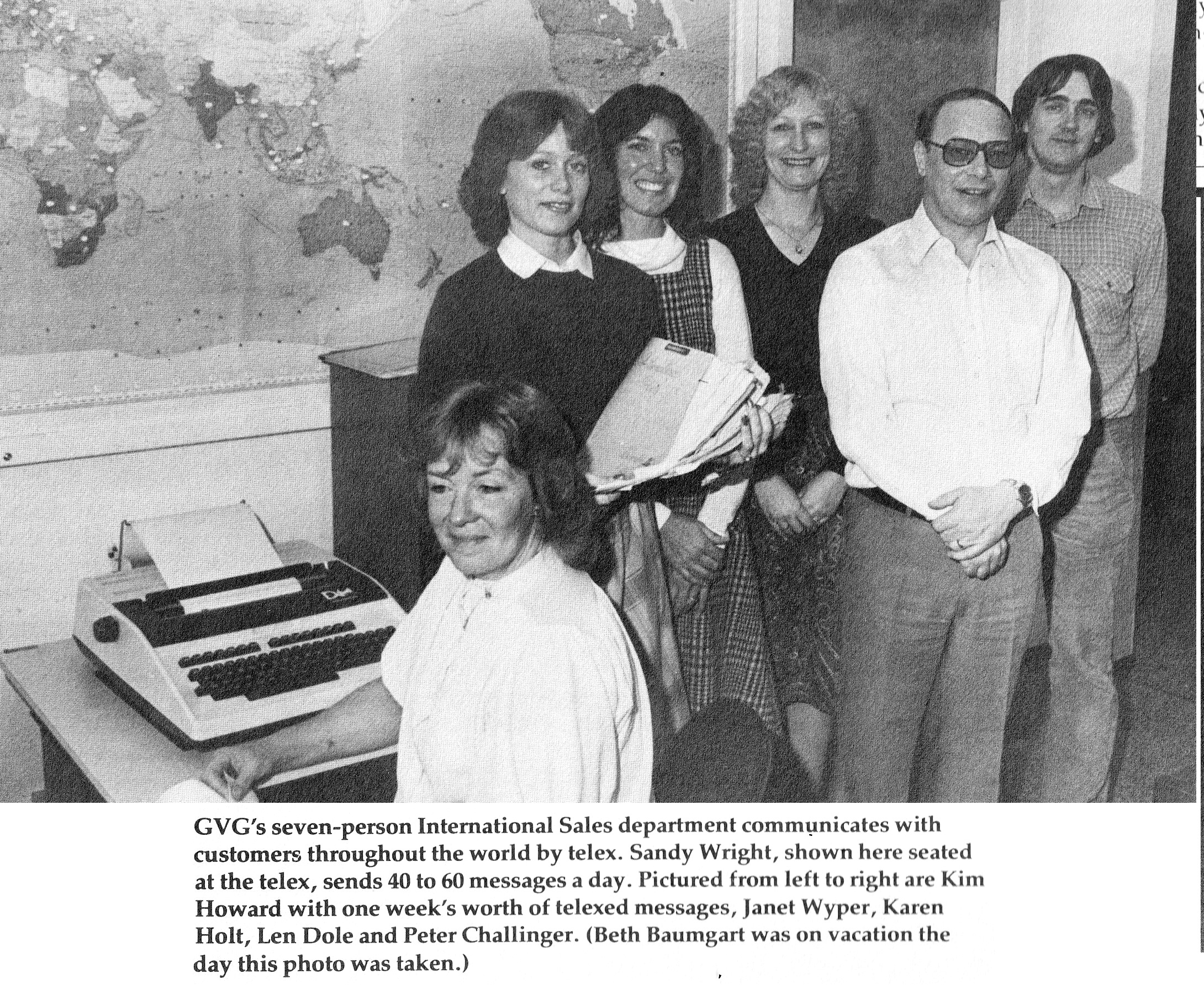

In 1979 the Group brought in $287M in sales. The next year that had been raised to $352M. He promoted Len Dole to International sales Manager. Dole was hired in 77. Up until that time sales were being handled by Tektronix's sales force. They did not know how to sell the Group's flagship product, video production switchers. Dole laid down the law about not using Tektronix and won. As we saw in the last chapter he did the same thing with Sony in Japan. He also demanded that the Group start producing more products that worked with the PAL television standard, and not solely concentrate on products for the American NTSC standard. In chapter 10 we saw how a PAL product was used in a way that infuriated Dole and his British compatriots.

International sales at the beginning of 1982

Under Friedley's direction by the end of 1981 the Group had a sales staff in the states of a little over 20, with about a dozen in the field. To minimize the company's dependence on a potential, and as it turned out, a future competitor, in November of that year the Group had its first European dealer training. Up until then Sony handled most of GV's sales internationally.

At the beginning of 1982 the Group established a five person service and support organization in Winchester, England. In August of that year the Group selected 25 distributors in the U.S. to help sell products in the non-broadcast market.

As mentioned, Friedley was the one who saw to it that Dayton's hybrid project got funded, and in 1982 promoted him to Director of Research and Engineering. Also that year, with a $117K grant, Friedley also signed on to help the local junior college, Sierra College to train electronic techs and assemblers over the next 2 years.

"Divisionalization"

A couple years after Tektronix bought the Group, Tek changed its own organizational structure. Up until then it was organized around specific product lines. Now it would be divided up into divisions based on large general markets. While the company still had centralized Manufacturing, R&D, and marketing and sales, along with a HQ corporate staff, there were four product divisions formed. The Instruments Division looked after the legacy products, mainly scopes. The Design Automation Division covered microprocessor development, semiconductor test, and logic analyzers. The Information Display Division covered just that, displays, and terminals, along with the company's nascent printer products. The Communications Division covered cable testers, spectrum analyzers, and anything related to television. That included the Grass Valley Group. The president of the Group, reported to Tom Long, who was VP, and GM of the division at the time.

In the fall of 1978, Dave Friedley replaced Jim Ward as the Group's President. He was sent down from Tektronix. This move cemented the integration of Tektronix's control over the Group. He was charged with trying a test case for "divisionalization" of the Group, that is breaking up the Group along the lines that Tektronix had done. The turmoil going on surrounding the 300 launch gave importance to trying the experiment. At the end of 1980 Friedley decided modular was a good bunch to try it on, since it produced enough product and was thus a classic production line operation. Whereas routers and production switchers were more like job shops, they were unique custom products.

Friedley also decided to totally separate this division and put the newly formed Modular Division out at the airport. Up until then all parts of the company used common engineering, production, and test. Modular became a totally separate and standalone operation.

Friedley also decided to totally separate this division and put the newly formed Modular Division out at the airport. Up until then all parts of the company used common engineering, production, and test. Modular became a totally separate and standalone operation.

Dan Wright was a manufacturing engineer in Tektronix's spectrum analyzer product line, which was part of the Communications Division, again the same division that the Grass Valley Group was a part of. In 1979, Friedley brought Wright down to the Group. Wright was to help get the switcher into production. While Wright was an accomplished technocrat, he was up against what the group's engineering was struggling with, they still didn't know exactly what they needed to build to make the 300 meet its advertised external specs. The final design of the 300 was a moving target until the end of 1981. Wright was successful in helping to iron out how to build the 300. That is when Friedley decided to "divisionalize" Modular, and he chose Wright as the general manager of the Group's first division.

The Modular Division had its own marketing headed up by Randy Hood, who later became its G.M., and its own manufacturing, which was headed up by another rising star, Dave Mayfield.

The Modular Division had its own marketing headed up by Randy Hood, who later became its G.M., and its own manufacturing, which was headed up by another rising star, Dave Mayfield.

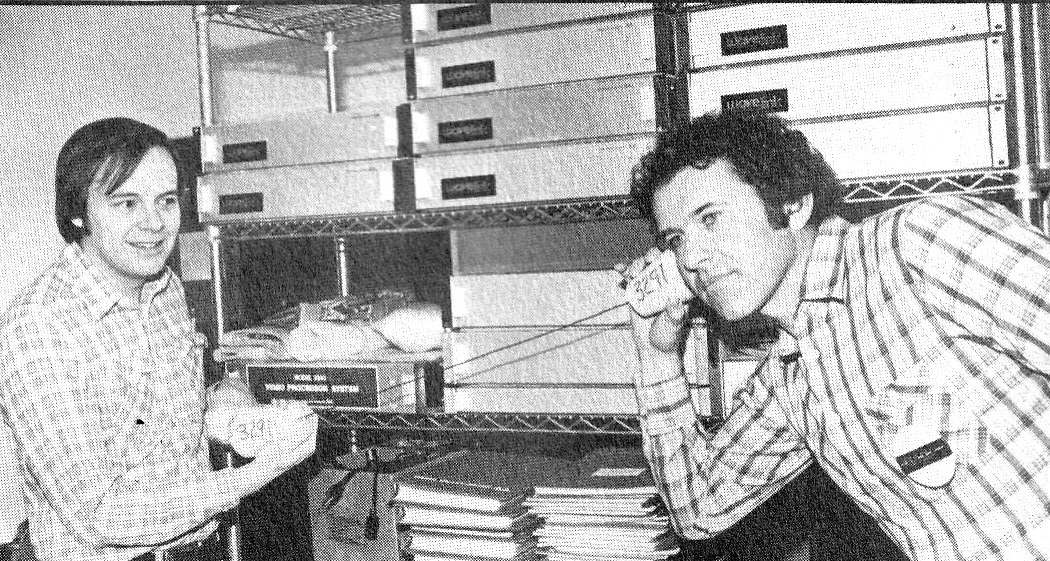

Jim Michener (left) and Randy Hood

Randy had no background in television and little background in electronics, before coming to the Group he had played AAA baseball. Dan Wright liked him for his hustle. So one Jim Michener's tasks was to mentor Randy. The photo was a playful example of how sound travels over a fiber optic cable. Hence the string and two cans.

To promote WaveLink, before it was made its own separate department, and to introduce Randy to GV's field sales force and some of the customers, Randy and Jim went on a multi week nine city tour where they gave a talk and demo of WaveLink at various Society of Broadcast Engineers (SBE) meetings. After about three of these, Jim felt like it was Ground Hog's Day. Randy wanted to see the major league baseball parks. Included in the tour was Atlanta, Cincinnati, Detroit, Kansas City, Washington, among others.

Before they left they did a dress rehearsal at an SBE meeting at nearby KCRA in Sacramento. Others from the Group attended and they polished the presentation. Afterwards there was a young kid, who was an intern who asked many questions. Jim eventually asked him what he did at KCRA. An intern in the news department was his answer. When asked why he would want to attend a "boring" SBE meeting, he replied that he wanted to learn what goes on behind the camera. Jim agreed that was a good thing. Jim then then asked him what he wanted to do after school, and he said, "I want to anchor the NBC Nightly News." KCRA was an NBC affiliate. "Okay," Jim said," by the way, what is your name?" "Lester Holt," he replied.

The Group still had a centralized manufacturing operation which was headed up by company veteran Jerry Sakai, who had the title of VP of Manufacturing. Sakai's group stayed centralized, as the machine shop, PCB fab, materials planning, purchasing, and warehousing provided those services to the other divisions. In some ways the concept was that Sakai's group would be an outsource entity to the divisions, and thus had to remain competitive with outside sources.

In June of 1981 two more divisions were carved out, the Production Systems Division (PSD) and the Broadcast Systems Division (BSD). PSD were switchers and associated products. PSD was the 800 pound gorilla as it comprised 60% of the Group's sales, and had 400+ employees, 200-250 in assembly alone. I've herd two versions of this: that modular was the gorilla and that it was PSD?

In some ways this move made sense in that PSD customers were more creative types, and they always wanted additional capabilities. Chuck Clarke, the divisions Marketing Manager said, "It's like the fashion industry, you have to be in style." This is in contrast to the MSD and BSD divisions, who dealt with more technical types than PSD did.

Leon Stanger (left) and Chuck Clarke

Leon Stanger, who inherited the 300 debacle became a Project Manager in PSD and reported to Ralph Barclay.BSD eventually became the Switching Products Division. They mainly made routers. Jay Kuca, who eventually became the company's overall marketing manager was the Product Marketing Manager of Routers.

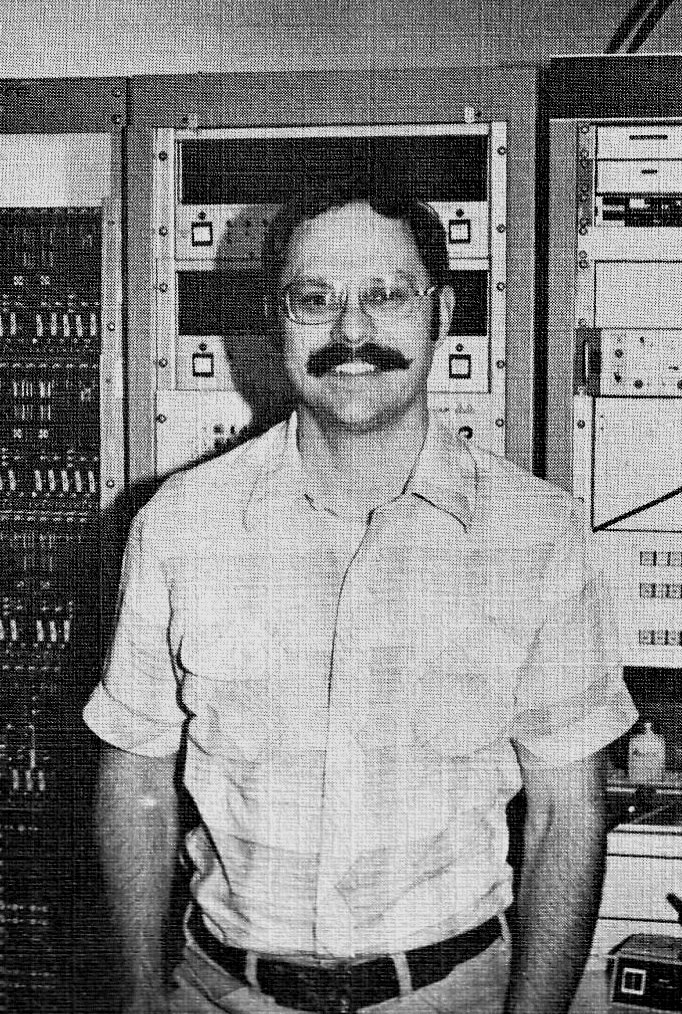

Dan Wright - Modular GM at the time

Wright was a true believer in separate product divisions, as before Tektronix had split up into divisions with their own separate engineering staffs he thought that the company's centralized engineering was too overbearing. In 1983, when Friedley left the Group for his promotion to Tektronix's VP of the Communications Division, he promoted Wright to succeed him as President of the Group. In that capacity, Dan continued Friedley's efforts to "Tekify" the Group. Eventually he would continue to follow behind Friedley as he eventually ended up running the Communications Division also.

Not everyone thought divisions made sense for the Group. The Group still had some common resources such as sales, PC fab, and metalwork. It would have been cost prohibitive to set up PC fab, and machine shops for each division. Also you need your sales force to be able to walk into a customer's facility, mainly broadcasters back then, and be able to sell everything the company had to offer. The only instance the Group had where they had a customer base that was not broadcasters, was with Wavelink, who generally sold to Telcos.

Another issue was an accounting one. The company had to deal with transfer pricing, that is how one division (on paper) pays another so that the finances stay separate.

One person who thought that the concept was taken too far was Birney Dayton. He ran the hybrid manufacturing operation until 1985, until Wright decided to spread that across all the divisions. As mentioned earlier Wright thought that Birney wanted to run his own business or division. He still had the title of V.P. of Engineering, but most engineering was now diversified across the divisions. So Wright kicked Dayton out of hybrids during divisionalization and put him in charge of Wavelink.

Most of the divisions had problems building hybrids as hybrid manufacturing was the most intricate operation the Group had. As said earlier it was halfway between PCB and ICs manufacturing. Dayton thinks that the only division that got their arms around it was Modular, thanks to the diligence and experience of Jerry Sakai, who oversaw that divisions implementation of it.

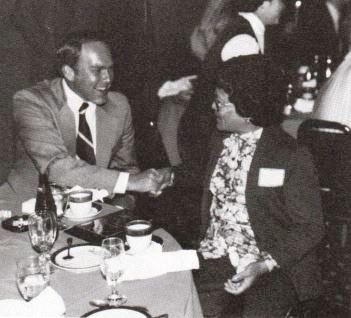

Jerry Sakai and Tom Long at a company gathering in July 81

Sakai, while V.P. of the company's manufacturing, he had oversight over the Modular division as Administrative Manager via the management council that Friedley had setup. This arrangement had Bill Rorden as the Administrative Manager of BSD, and Bob Cobler the Administrative Manager of PSD. It is interesting to note that Sakai and Rorden were engineers, while Cobler was in marketing. It would lead credence to what Chuck Clarke said a few paragraphs ago.

Friedley's management council in 1981.

Left to right: Rorden, Cobler, Fenner, Friedley, and Sakai.

When the Group was completely split up into divisions it was organized as follows:

1) Modular Products Division - This division made all the modular "glue" products

2) Production Systems Division - which eventually became the Professional Video Division. They made switchers. Next to Modular this group was the closest to a regular assembly line operation, as the smaller production switchers were far more off-the-shelf products than high end switchers and routers. While the high end switchers were much more of a job-shop operation making highly customized, expensive products. It accounted for 60% of the sales, the other two had about 20% each. This division had at its formation 400+ employees, over 200 in manufacturing alone, out of a total of 925 total employees at the time.

3) Broadcast Systems Division - which eventually became the Switching Products Division. This group made routers, automation, and ancillary products like 10 by 1 small switchers.

4) Wavelink - which was a part of MPD

Actually Grass Valley's Divisions were "hybrids." Divisions make sense if there's no common resources such as sales, PC fab, or metalwork. With Grass Valley this was not the case. The only part of the company that had a separate sales force was Wavelength because it sold to a different clientele. The divisions did have their own engineering, manufacturing, and test. But the service force was still one group under Corporate Marketing.

After building 9 was completed in 1982 it was occupied by PSD, along with the machine shop and PCB fab. The company's PCB fab operation was an asset into the 80s as Tektronix was also paying to use it. In 82 it gave the Group an order for 3,200 PCBs for a new product they were producing.

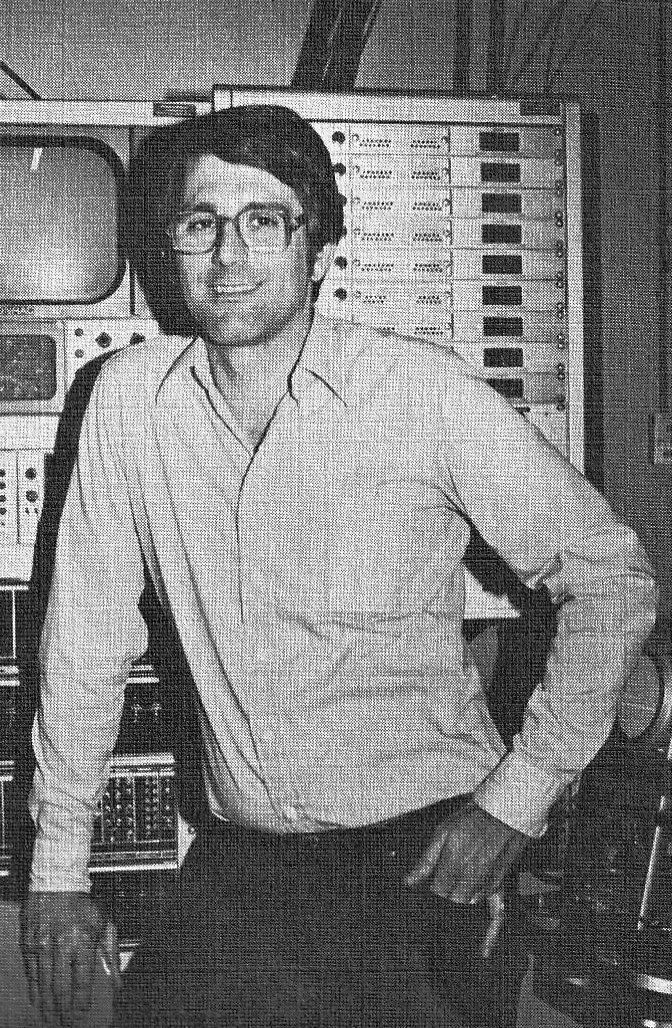

Denny Ebner and Jim Tetzlaff

Now that the company was divided up into divisions it made for a more complex management structure at the Group. In 1982 the hierarchy was the three divisions. MPD's Division Manager was Dan Wright, BSD had Denny Ebner as its GM, and PSD had Jim Tetzlaff. There also was a Corporate group that was comprised of accounting and legal. But in keeping with the hybrid "divisionalization" model, there were still VPs of Manufacturing, Engineering, and Marketing, held by Jerry Sakai, Bill Rorden, and Bill Cobler respectively.

Those three positions were part of a "management council." Also on that council was Greg Fenner, VP of Finance and Planning. Dave Friedley the highest ranking officer at the Group as Executive VP, ran the council. Between each Division's GM there was an Administrative Manager, a VP on the management council. Sakai was over Wright, Rorden over Ebner, and Cobler over Terzlaff.

(A bit fuzzy on this) There were a couple exceptions. The group that was making hybrids, run by Corporate Component Development Manager, Birney Dayton, who reported to Rorden. The other was the Tech Arts and publications who also reported to Sakai. In addition, Facilities Manager Ken Myers reported directly to Friedley.

At the time a number of people who would go on to play important roles in the company, and in other future companies were in prominent positions spread among the divisions. Dan Wright, and Dave Mayfield, future Grass Valley leaders were MPD's GM and Manufacturing Manager respectively. Randy Hood, MPD's Marketing Manager was also under Wright. Hood would be predominant in a later startup company in the area. Jay Kuca, who eventually would head up the company's marketing effort was BSD's Product Marketing Manager. Jay went on to a prominent startup in the area.

But problems were starting to to gather and grow. The catalyst was what the company had thrived on up until then.